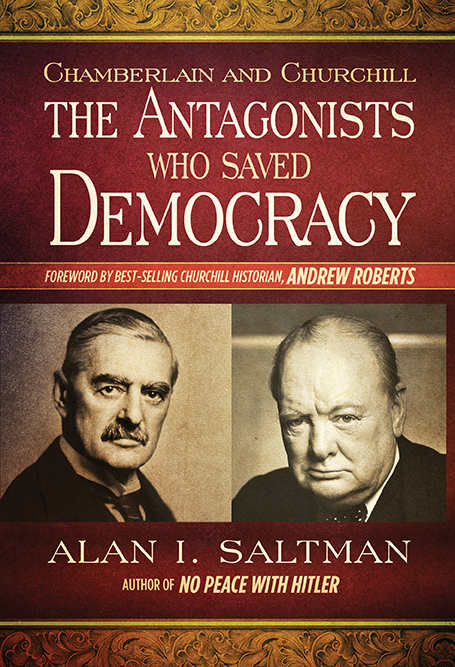

Alan Saltman, Chamberlain and Churchill: The Antagonists Who Saved Democracy (United States: WG Hobart Publishers, 2025).

‘Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill between them saved the country. Neither statesman would have achieved our salvation without the other,’ Conservative MP Patrick Donner once commented. With this new study, Alan Saltman explores the relationship between Chamberlain and Churchill and how they came to be the antagonists who saved democracy. Using methods of psychohistory and an array of public and private papers, Saltman recognises the importance of understanding the statesmen’s backgrounds, aspects of their youth and their differing opinions over their 20-year professional relationship to understand how they came to be the men they were in the wake of Hitler’s rise.

In a thought-provoking analysis of their youth, Saltman questions the impact of their traumatic childhood on their characters as politicians. Both experienced, in some ways, a lonely childhood. Churchill felt neglected by his mother’s indulgence in society life, and Chamberlain suffered the loss of his mother when he was only six years old. Their respective fathers were so heavily involved in their politics that neither had much time for their sons. Although Chamberlain had his siblings to ensure a happy boyhood, outside the family circle, he appeared uncomfortable and shy. Saltman assesses the impact of this on their later character concluding for Churchill his loneliness made him self-confident and outgoing contrasting with Chamberlain who was visibly retiring in his shyness.

Evaluating these family relationships, Saltman provides a psychoanalytical assessment of how both men felt they had to prove themselves to their dead fathers through their political careers. Lord Randolph Churchill was dismissive of his eldest son and commented that his younger son, Jack, was ‘vastly his [Churchill’s] superior’. Chamberlain was similarly aware he was not his father’s favourite son. His elder brother, Austen, was the one who was groomed for a glistening political career. Both men also felt the grievances of their early misdeeds. For Churchill, it was Gallipoli, and for Chamberlain, his failure to restore the family’s fortune at the sisal plantation in the Bahamas. Establishing themselves on the political platform allowed them to prove themselves in their father’s eyes and attempt to obtain redemption for their earlier failures.

In their early political careers, their father’s legacy was influential but also challenging as they tried to make a name for themselves. In 1921, Chamberlain wrote in his diary, ‘It is a great handicap to be the son of my father and the brother of my brother, for every success is discounted and every failure is counted double.’ Although Churchill did not face the same constraints as his father’s death had left the floor open for him, the same could not be said for Churchill’s son Randolph in years to come. However, Churchill worked tirelessly to match his father’s achievements and reestablish the Churchill name in the House of Commons. During this period, Saltman argues that although Chamberlain and Churchill were not close allies, they maintained mutual respect. In 1925, Chamberlain praised Churchill’s work as Chancellor in his diary, writing ‘Winston’s exposition of the Budget was a masterly performance.’ During the second Baldwin administration, they often clashed. Chamberlain refers to Churchill as this ‘brilliant, erratic creature’ in his diary and in letters to his sister as Chamberlain and Churchill competed to demonstrate their value as contenders to succeed Baldwin as party leader.

Providing an assessment of the two men’s attitude to appeasement, Saltman argues that Chamberlain naively came to believe he could negotiate with Germany with him recording, ‘These dictators are men of moods. Catch them in the right mood and they will give you anything you ask for.’ Chamberlain wanted no stone unturned to avoid war. However, as Saltman rightly points out, despite believing he could negotiate, Chamberlain was no fool, and although he longed for peace, he prepared for war simultaneously. Around the time of the Munich Agreement, Chamberlain wrote to his sister, ‘Is it not possibly horrible to think that the fate of hundreds of millions depends on one man and he is half mad?’ His optimism was perhaps dwindling, but he pushed on in an attempt to secure peace. As Churchill wrote in The Gathering Storm, Chamberlain hoped he would ‘go down in history as the great Peacemaker’.

As Saltman demonstrates, the period after Munich was the lowest in the Churchill-Chamberlain relationship. Churchill maintained that Britain must take a firm stand with Hitler. He launched bitter attacks against Chamberlain, the now prime minister, arguing that, between war and dishonour, the PM had ‘chosen dishonour and would have war’. As a result of the constant attacks, Chamberlain remained adamant that he did not want Churchill in the peacetime Cabinet. Comparing the contrasting views between Chamberlain and Churchill during this period, Saltman questions why the men thought in this way and how previous experiences and early lessons had led to these conclusions and stances.

Throughout this study, Saltman develops a comprehensive assessment of Chamberlain’s personal correspondence with his sisters to understand his moods and actions. Historians have argued that these weekly letters reveal ‘a personality that marked traits of inferiority and hunger for flattery that nursed a growing vanity [which was strong yet childlike], and self-righteousness.’ However, as Saltman proves they also tell the story of Chamberlain’s changing moods and relationship with Hitler, his determination to secure peace, and the pressure he endured as he stood to prove his worth, not only to the nation as prime minister but to his dead father. Reflecting on the struggle of being prime minister during the imminent threat of war, Chamberlain wrote to his sister Hilda that he envied the peace his late brother Austen enjoyed as he again compared himself to his siblings and father’s political success. Saltman’s examination of these letters provides a fascinating insight into Chamberlain’s psychology and mindset during a pivotal time in his career.

Thoroughly researched and expertly written, Saltman offers a captivating study of the extraordinary relationship between Chamberlain and Churchill, highlighting the crucial steps they took in their efforts to save democracy. This assessment details how they each served one another and how their collaboration and differences changed the course of history.

Leave a comment