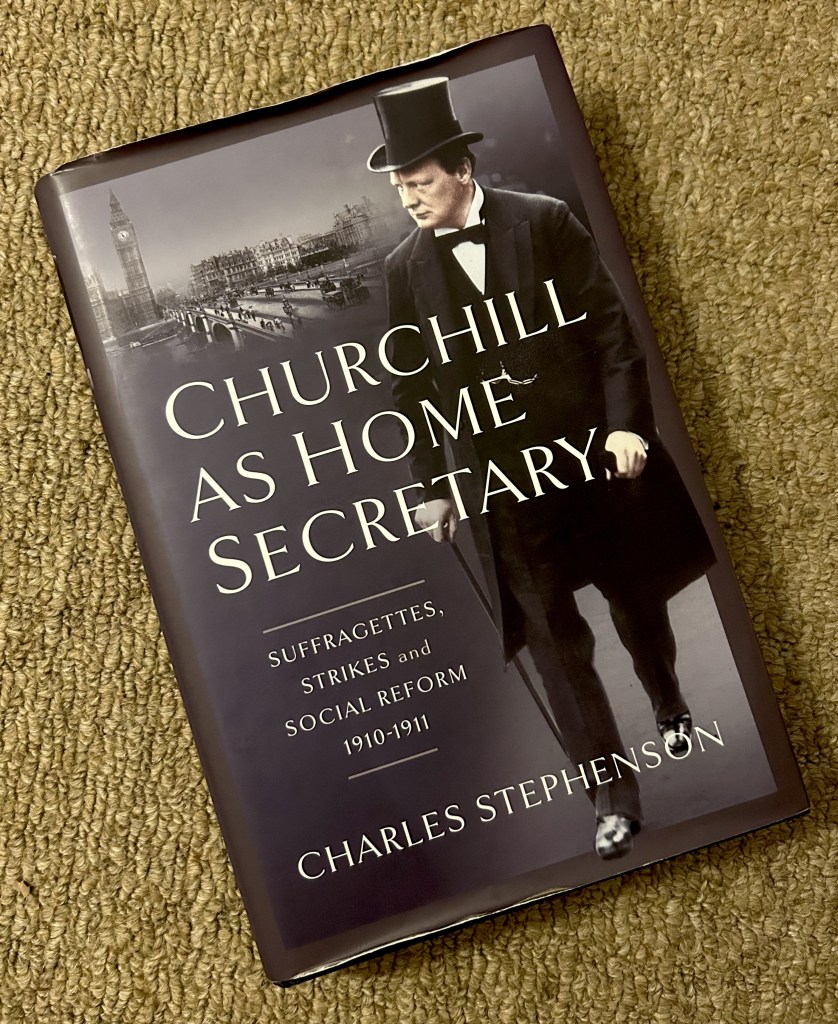

Charles Stephenson, Churchill as Home Secretary: Suffragettes, Strikes and Social Reform 1910-1911 (Great Britain: Pen and Sword History, 2023). RRP: £25.00

In the extensive and vast study of Sir Winston Churchill, Churchill’s contribution as Home Secretary has been largely overlooked by historians. In this recently released study, Charles Stephenson delves into this lesser-known aspect of Churchill’s life, exploring and evaluating his crucial position as Home Secretary over his twenty-month tenure. Analysing various archival materials, including newspapers, diaries and personal correspondence, Stephenson sheds light on Churchill’s policies and actions during this period. Embarking on the Home Office, Churchill was the youngest politician to hold the post since Robert Peel in 1822. A large task lay ahead of him. It has been noted that ‘Home Secretaries never do have an easy time,’ a remark that Stephenson proves was true for Churchill.

Throughout the study, Stephenson tackles various challenges Churchill faced during his tenure, including the Newport and Tonypandy strikes, prison reform and the Suffragettes. On prison reform, Stephenson reveals Churchill’s significant contribution to reducing the number of people committed to prison and how he campaigned for shorter sentences and better treatment for those who were admitted. Having been held as a prisoner of war during the Boer War, it can be argued Churchill sympathised to a certain degree and sought to create a safer environment for those in rehabilitation. As Violet Bonham Carter reflects, Churchill was seen as the ‘Prisoners friend.’

In his battle to improve reform, Churchill faced some opposition, as Stephenson assesses. As a junior in the Home Office, Harold Butler recalled, ‘The old hands in the department were rather dismayed by the temerity with which he challenged principles and the practices which had remained sacrosanct for many years…’ Churchill was to find that at times his power as Home Secretary was strictly limited, causing some frustration and limitations to the extent of his success.

Stephenson concludes the belief that Churchill’s tenure as Home Secretary was an ‘unhappy’ one is indisputable and that to argue he was ‘temperamentally suited to the role would hardly be contentious.’ Many studies have assessed the ‘black dog’ Churchill experienced between 1910 and 1911. Stephenson writes that although it was a period where Churchill was ‘happily married’ and ‘undoubtedly famous’, he was also bitterly criticised and disrespected by the press as the government were attacked for their inability to ‘keep the trains running’ during national unrest. Consequently, the situations and tasks he faced lay heavy on Churchill’s mind.

This study is a valuable addition to the existing literature on Churchill’s life and legacy; Stephenson successfully provides the reader with an in-depth insight into the ideology and leadership Churchill exercised in the Home Office and how the skills he developed ultimately formed him into one of the most prominent figures in modern history.

Leave a comment