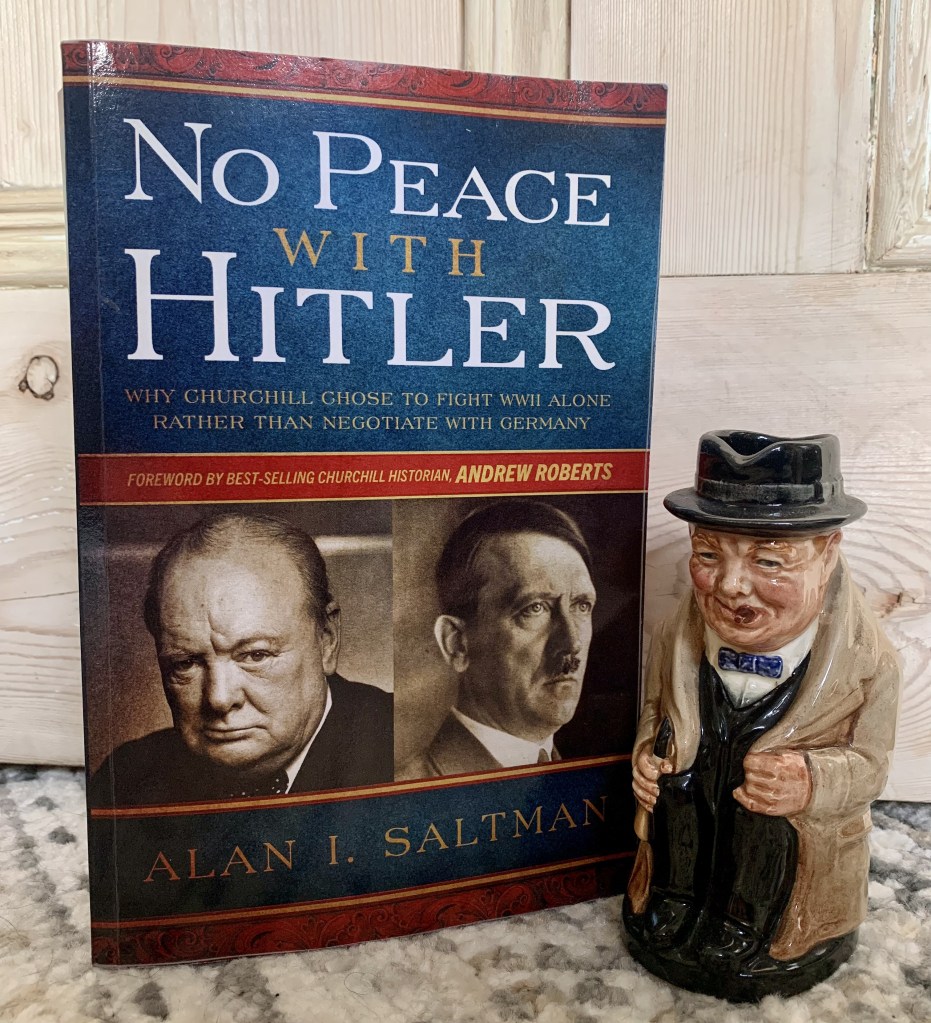

Alan I. Saltman, No Peace with Hitler: Why Churchill chose to fight WWII alone rather than negotiate with Germany (United States: WG Hobart Publishers, 2022). RRP: $35.99

On 10 May 1940, Winston Churchill became Britain’s Wartime Prime Minister writing that, ‘…all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.’ It is this ‘preparation’ that Alan Saltman assesses in this well-researched and highly detailed book. Using methods of psychohistory, and a vast array of sources, Saltman seeks to unearth how Churchill’s past life had in fact prepared him to rightly refuse to negotiate peace with Adolf Hitler in the months and years ahead of him as Prime Minister.

Developing a sophisticated analysis of Churchill’s life, Saltman questions what provided Churchill with this deep understanding of war. Assessing Churchill’s early years and early career, Saltman demonstrates to the reader the stages of Churchill’s early interest in military campaigns. Churchill is depicted as a young child arranging his toy soldiers ready for battle and later entering Sandhurst as a cavalry cadet in 1893. Churchill at many stages of his life was actively involved in warfare, whether that be through actively fighting, corresponding or at times politically as he held a range of defence positions in the cabinet. Saltman argues that the lessons Churchill learnt through these roles were vital to forming his stance on Hitler and his refusal to negotiate peace. Churchill, more than many in the House of Commons, understood the course of war and what it meant for Britain, and world democracy if the allies did not fight on. Furthermore, throughout his wilderness years, Churchill had witnessed how Hitler had already broken all previous peace negotiations and was a man who could not be trusted. ‘War, more than life, was the chess game in which [Churchill] could see several moves ahead’, Saltman writes. It is evident throughout the book that Churchill possessed a much clearer understanding of Hitler’s aims than many during the 1930s but his warnings were met with criticism and he was labelled as a ‘fear monger’. His intuition and warnings proved to be right and as Saltman comments the responsibility to know the next move would soon fall upon him.

Referring back to Churchill’s early years, Saltman further demonstrates Churchill’s attitude towards bullies and how to deal with them. Churchill recognised Hitler’s unstable and erratic nature of terror and knew that the only way to deal with such a bully was to confront them. Churchill had dealt with bullying from an early age whether that be from his contemporaries at school, teachers, and even at times the bullying nature of his father. Saltman argues that by having had these ‘personal experiences’ with bullies and having the ‘wisdom to declare Hitler early on as being irredeemably treacherous’, Churchill had ‘no compunction about fighting him in a war’. Saltman further remarks that how to fight the war was complex, but for Churchill, the reason ‘why’ to fight was very clear.

Using psychoanalysis, Saltman assesses how childhood relationships impacted Churchill’s thoughts and actions in later life. One key relationship for this is Churchill’s often distant and complex relationship with his parents. It was the difficulties in this relationship which gave Churchill the longing to be a devoted and doting parent himself. Churchill hoped to present himself as an empathetic figure able to provide those around him with the same love and affection he had received at the hands of his nanny, Elizabeth Everest, whom he called ‘Woomy’. Saltman accurately writes that during the war years, Churchill also became the parent of the nation. The public looked to Churchill for guidance, courage, and hope, as he presented them with a deep and compassionate affection, something evident in Churchill’s Blitz Tours around the country. As Saltman comments, Churchill became ‘Britain’s Woomy’.

Furthermore, Saltman also provides the reader with a detailed insight into the developing relationship between Churchill and Neville Chamberlain. In the 1930s, Churchill heavily criticised Chamberlain’s policy for Appeasement in the House of Commons and argued for Britain to rearm. Saltman demonstrates that the shift in this relationship came when Britain announced war on Germany on 3 September 1939, and Chamberlain invited Churchill into the War Cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty. Saltman argues that from this point Churchill turned from an ardent critic of Chamberlain to a loyal supporter. Chamberlain later repaid Churchill for his ‘intense loyalty’ when he succeeded him as prime minister. In May 1940, Chamberlain was now seen to favour Churchill’s policy of ‘fighting on’ over peace negotiations, a policy still being pushed for by Lord Halifax, the man who Chamberlain had originally hoped would succeed him as premier. Saltman puts this change in Chamberlain’s thought process down to two factors: (1) Chamberlain acknowledged that this approach in 1938 and 1939 had not worked and he was made to look ‘the fool’, vowing it would never happen again, and (2) he did not trust Hitler to keep his word. This new friendship and loyalty with Chamberlain proved crucial for Churchill as it would provide him with further unity in the war cabinet and would face much less opposition.

Through extensive research, Saltman provides the reader with a detailed and well-analysed insight into why Churchill chose not to negotiate peace with Germany arguing that the only way to achieve real peace was to fight on, “…if necessary, for years, if necessary, alone…” With a psychoanalytical approach, Saltman assesses the personal experiences Churchill faced throughout his life which impacted his approach to finding peace and how crucial his courage was to stand alone during the nation’s hour of need.

Leave a comment